Read the article here: Boston Voyager

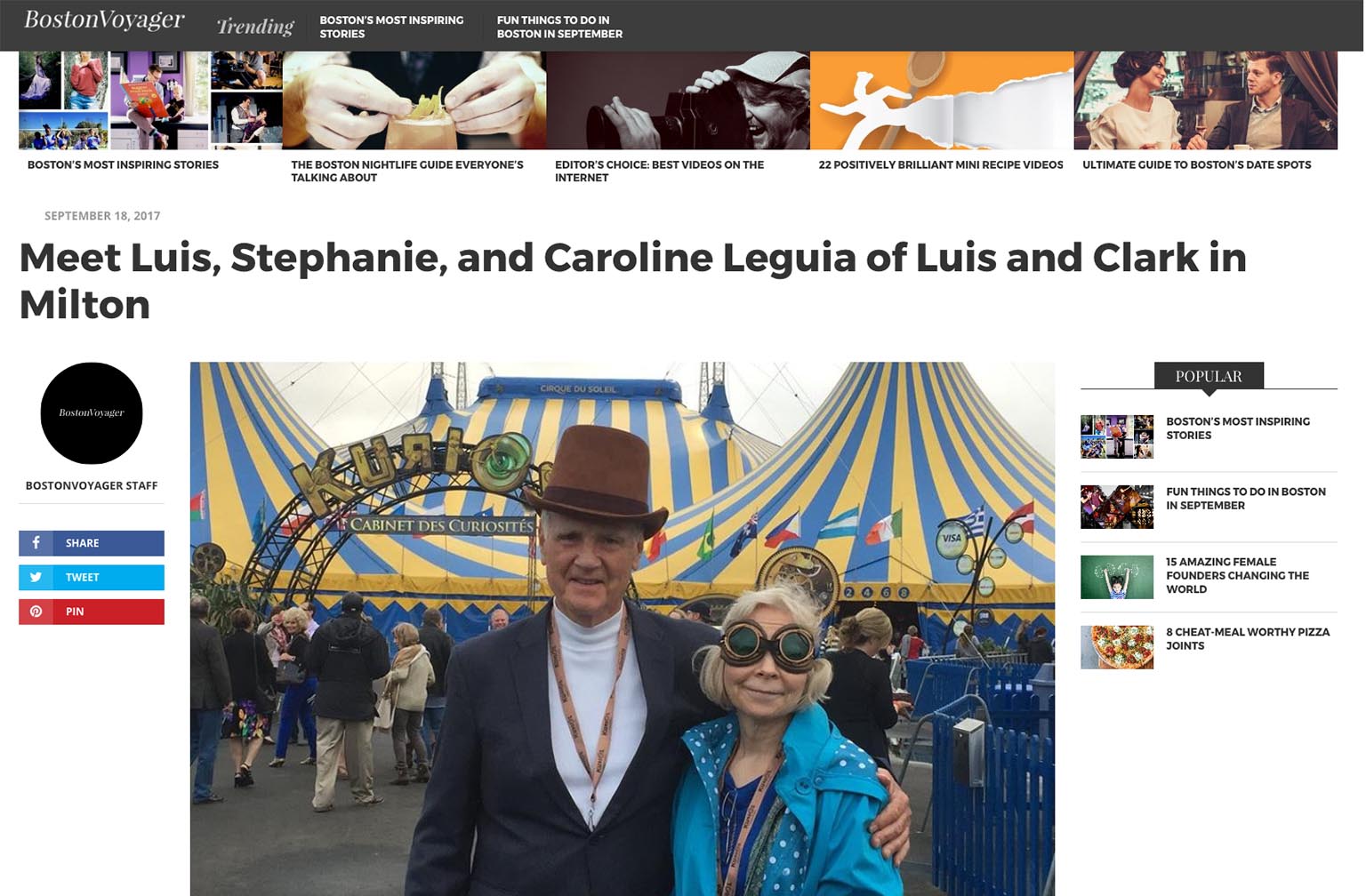

SEPTEMBER 18, 2017Meet Luis, Stephanie, and Caroline Leguia of Luis and Clark in Milton

BostonVoyager Staff BOSTONVOYAGER STAFF

SHARE TWEET PIN

Today we’d like to introduce you to Luis, Stephanie, and Caroline Leguia.

Luis, Stephanie, and Caroline, can you briefly walk us through your story – how you started and how you got to where you are today.

Caroline: The story of Luis and Clark is the story of my father, Luis Leguia. The carbon fiber string instrument is his invention. Growing up in poverty, the son of a single mother (his father had returned to Peru when he was three years old), living in boarding houses, struggling in life and in school, music was one thing in which he excelled. He had scraped together $100 from his paper route to buy a cello and began studying with Arthur Van den Bogaerde, Principal cellist of the Disney Orchestra and a former student of Pablo Casals, who was kind enough to give him free lessons, sometimes three times a week. Starting his cello studies at almost 15 years old, my dad could be considered a very late beginner, but his incredible work ethic soon saw him practicing 6 to 8 hours a day, working late into the night alone in a small closet with many clothespins clipped onto his bridge as a makeshift mute, all while working full-time to help support himself and his mother.

Eight months into his studies, Arthur (at this point my dad’s mentor and father figure as well as his teacher) was tragically struck and killed by a car. At this point, my father was working 36-40 hours a week and attending school once a week for four hours in a special program for working students. He began studying with Cy Bernard and later Kurt Reher (Principal Cello for 20th Century Fox and the Los Angeles Philharmonic). In the summer between his studies with Bernard and Reher, my father was granted a scholarship to Music Academy of the West, where he met Gabor Rejto, a cello professor from Eastman who wrote my father a letter of introduction to Pablo Casals. Less than two years after beginning his cello studies, and against all odds, my father was fortunate enough to become a student of Pablo Casals (arguably one of the greatest cellists who ever lived) at a time when Casals wasn’t even taking students! My father had never stepped foot out of California and didn’t speak a word of French, but with a final payment from his father (intended for the purchase of a better cello), he instead bought a ticket on a boat to France and never turned back.

After studying with Casals for a year and a half, my father went on to study at L’ecole Normale under Andre Navarra and then, for a short while and with a full scholarship, at Juilliard under Leonard Rose. Knowing that he would never be able to graduate with a diploma due to his lack of a high school degree, my father left Juilliard, completed basic training, and joined the Army Band. He later played the cello in the National Symphony, the Houston Symphony, and the Metropolitan Opera. He joined the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1963, where he played for 44 years while maintaining a busy solo career.

My father made 15 solo tours of South America and took a sabbatical from the BSO in the winter of ’84-’85, making recital and concerto appearances in Portugal, Berlin, Tubingen and Belgium, and, most notably, performing the complete Cello Suites of J.S. Bach in Madrid, Spain. He has performed premieres of many pieces, had works dedicated to him and written expressly for him to play, and even performed the Kodaly Sonata (one of the hardest works written for cello) for Kodaly himself! During this performance, my father experienced one of the most alarming sensations a cellist possibly could: he was playing outdoors in extreme heat, and, as the glue began to melt, the neck of his cello started slipping away from the body while he played! A harsh reminder of what the climate can do to wooden instruments…

Back when my father was studying with Leonard Rose, he needed a better instrument than the one he was playing, and fell in love with a cello that he thought had a gorgeous sound. He brought it to Rose to see what he thought, but when he played it for him all he got was, “You won’t hear that cello past the sixth row, Louie.” This had a profound impact on him. Despite having played many fine cellos that he loved over the course of his career, he had never found one that truly satisfied him in its ability to project, as a solo instrument, over an orchestra or a grand piano.

My dad became an avid sailor in the ‘70s and one afternoon while on his catamaran (a small boat consisting of two hulls and a trampoline between them), he heard a resonant humming sound. He realized that the sound was created by the vortex of the waves against the carbon fiber hulls of his hobycat. More importantly, he noticed that the sound of waves against carbon fiber boats was louder than it was against wood! It occurred to him that perhaps he could construct a cello from the material.

An amazing trait my father has is his ability to recall every detail about any instrument he has ever played. He can name its owner, when and where he played it (and often, who was conducting), the name of the maker, the year it was made, its physical characteristics (from the color of the finish to the width of the upper bout), and – most importantly – the qualities of its sound: whether it was bright or dark, whether it had a particularly sweet tone or a very deep one, and – always – its ability to project. He taught himself to recognize which physical attributes created the sound he loved in his favorite instruments, and invented a cello for himself based on these attributes and his understanding of how subtle changes to the design of an instrument can completely change its sound.

My father began experimenting building his own cellos with new-age materials in 1990, the year I was born. When he started I still remember riding around on my tricycle, “helping” him while he worked, and getting the occasional speeding ticket before being sent upstairs while he donned a ventilator to work with the epoxies. He built three prototypes by hand on a sheet table in the basement, the first prototype in fiber glass and the second and third in carbon fiber. Taking a bold step away from its predecessors, the third prototype did away with the cornices (corners around the middle bout of the instrument), leaving the beautiful streamlined curvy silhouette now characteristic of our instruments.

Five years after he started this project, my father Luis approached Steve Clark, a master in the production and fabrication of carbon fiber products and chairman of Vanguard Sailboats. They partnered and formed “Luis and Clark,” pioneers in their field. With Matt Dunham at Clear Carbon and Components, they perfected my father’s molds to make them commercially viable. In 2002, they incorporated and went into production. Since then, my father has invented the carbon fiber violin, viola, and double bass. We’ve just started producing half size cellos, and we have a guitar on the way!

In the beginning, my father was just seeking to build the ultimate instrument for himself, but now we’ve sold over a thousand cellos as well as hundreds of our other instruments and we have owners in 54 countries.

Overall, has it been relatively smooth? If not, what were some of the struggles along the way?

Luis: Well, let me say that I started my work on a broken card table in an unfinished cellar with a single light bulb over my head. I knew very little about composite construction in the beginning and had to educate myself before I could even begin. And then there are the moments when all your hard work is about to pay off, and suddenly it seems like it’s all over… Just when I thought I had finished my first prototype, I realized it wouldn’t come out of the mold! It was a cold wintery day and I left it (mold, cello, and all) out on the porch upside down while I went to rehearsal. When I got back, I lifted it up and heard the “pop” of the cello releasing from the mold. What a relief! This whole process has certainly taught me patience.

Later, when I had perfected the design of the cello and went into business, I was met with resistance. As Henry Ford remarked, “If I had asked what people wanted, they would have said, ‘faster horses.’ But once people started buying them and other people saw them, the business grew quite quickly. The Internet was just taking off at the same time, so having people from all over the world be able to talk to each other was remarkable.

Stephanie: We are, and always have been, a small, family run company. We have a fabricator, a small team of expert luthiers, and a web design company, but other than that everything is done in house, by me, Luis, or our daughter Caroline. We often get requests from people asking for free instruments, not understanding just how small we are, and that it isn’t possible for us financially. There’s unfortunately a perception that we can give away instruments in exchange for exposure or testimonials, although we never have, and would consider it morally wrong to do so.

There are now imitators, of course, but musicians should never compromise on their sound quality and, as musicians, we certainly don’t. Maybe we could have made more money moving production overseas or using cheaper materials and components on our instruments, but we have a top-notch fabricator here in the U.S. and we are committed to making our instruments from 100% carbon-epoxy matrix. Each is set up carefully by hand with the highest quality bridges that are hand-carved to fit each unique instrument, and we play each one before sending it out. Keeping our instruments affordable without sacrificing quality in this economic climate is certainly a struggle, but we feel it is worth it.

Caroline: Our biggest struggle has (of course) been the cultural stigma against non-wooden string instruments. Music has a beautiful, rich history, people definitely love traditional approaches, and we totally understand people’s trepidation. But I’m always reminded of how the Boston Symphony Orchestra was the first orchestra in the world to have blind auditions – the musician would perform behind a curtain, in order to remove the cultural bias, the audition committees had against female musicians (and women were instructed to remove high heels so they could not be heard walking across the stage). After these auditions, the amount of women in the orchestra skyrocketed.

I’ve personally encountered closed-minded musicians who, without ever hearing our instruments, perceived them as “other” and inferior to wood. I’ve played juries where one of the judges refused to evaluate my playing because of it, which is just silly. Even traditional wooden string instruments come in many shapes and colors, and nobody minds a violin with a light finish next to one with a very dark one. It should always be about the sound, and if you close your eyes, our instruments sound like very fine wooden instruments. We always recommend blind sounds tests with our instruments, if possible.

I think there’s also a misconception Luis and Clark instruments were designed as an “outdoor instrument” to stand in for wooden instruments that people wouldn’t dare to play outside. That is putting the cart before the horse. My father was a world-class cellist and truly designed the cello as a solo instrument for himself; the company bloomed out of that. The sound has always come first, and the durability and resistance to changes in climate are just happy side-effects of using a material that is both more resonant and more durable than wood. It is not merely the material, but also the design that makes them sound so good.

Luis and Clark – what should we know? What do you guys do best? What sets you apart from the competition?

Luis: We make and sell carbon fiber string instruments. We were founded in 2002 after I invented the carbon fiber cello. I then went on to design a carbon fiber violin, viola, and double bass. We are known for the high-quality sound of our instruments and our great, personable customer service (a.k.a my wife, Stephanie Leguia). I am proud of inventing a beautiful and professional quality instrument that we have been able to put in the hands of many musicians who would otherwise not be able to afford one. I’m definitely the proudest of the sound, but you won’t hear any complaints about the durability!

Stephanie: We are very proud to be made in the U.S.A. We’ve had offers from people overseas who claim that they could make them cheaper, but we’ve never compromised on quality and it would feel wrong to make money on the backs of hard working people who don’t get paid a living wage.

We’ve supplied two Make-A-Wish recipients with cellos, which was amazing to be able to do. We also worked with an independent donor to provide instruments and supplies to musicians in the Congo. Many of our players have used our instruments in their own philanthropic endeavors, including ascending Mount Kilimanjaro with our instruments and helping to build a school there. Most of all, I’m proud of being able to share Luis’ incredible life work with such wonderfully talented musicians.

Caroline: I’m EXTREMELY proud of what my dad was able to do with little formal training. I find it very inspirational to share his story, and often tell people that it’s never too late to start!

I’m also very proud of the fact that we do not use the endangered wood ebony in our fingerboards, nuts, and saddles (instrument anatomy that traditionally IS made from ebony). Our instruments are also 100% vegan, whereas their wooden counterparts are made with animal glues. I think we have a very strong sense of ethical responsibility and I am very proud of that.

As a musician and someone who has a lot of physical problems, I also really appreciate how easy our instruments are to play! The viola is extremely light (1 lb. 4 oz.) which is unheard of and fantastic for an instrument that is typically very heavy and held under the chin, the lack of cornices on the cello allows it to sit closer to the body and to be easier to bow, and all the instruments have an ergonomic design that makes them much easier on the body to play. Couple that with their increased resonance, and you really don’t need to work very hard to draw a big, beautiful tone. It has been wonderful over the years to hear from people who had thought they were going to have to stop playing, or who actually had stopped playing entirely, and that we were able to give music back to them! That is the greatest gift of all.

What is “success” or “successful” for you?

Stephanie: I would define success as when you’ve enriched somebody else’s life.

Luis: First and foremost, having made a very fine instrument. People buying them and loving them, I think, is a product of that.

Caroline: I think the best measure of our success is all the fantastic musicians playing our instruments. Hearing soloists playing our instruments has always felt very special and affirming: Yo Yo Ma has owned a cello from the very beginning (he has #4), Canadian cellist Shauna Rolston has also had one from very early on, and Mihai Marika won an international cello competition playing his L&C. They also make great touring instruments due to their impervious attitude where climate is concerned, so groups such as One Republic and Hozier as well as players like Lindsey Stirling, 2Cellos, and The Piano Guys, as well as players in Cirque du Soleil have brought them to the forefront.

We are still sometimes met with resistance from traditionalists, but this is less of a problem than it used to be as they have built a reputation as instruments that can hold their own with the great old Italian instruments. With more and more of our instruments being played in orchestras every day, I think we’ll be seeing a lot more acceptance from the next generation.

Contact Info:

Website: https://luisandclark.com/

Phone: 617-698-3034

Email: info@luisandclark.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/luisandclark_instruments/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LuisandClark/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/luisandclark2

Other: http://luisandclark.tumblr.com/

Read the full article here: Boston Voyager